by Jennea Frischke

Have you ever thought about what bird tongues look like? They are very different from our tongues. Human tongues are primarily muscular, while bird tongues are rigid, and supported by bone and cartilage.1 Tongues are often very different between different bird species. Their tongues are a fascinating example of adaptations made over generations to help birds better thrive in their unique environments. Just within the woodpecker family, there are many differences in appearances and adaptations with their tongues.

Certain species of woodpeckers have very long tongues, that can extend several inches. Depending on what type of diet the woodpecker has, the tongue helps them retrieve their food (bugs, grubs, and sap for example). Since many woodpecker tongues are so long, they have a special storage space built into their anatomy, where the tongue coils up behind their brain (but not in contact with the brain). This Y-shaped structure consists of stiff, yet flexible, cartilage and bone connected to their tongues called the hyoid apparatus.1 This extra cushion behind the brain also helps absorb the impact from pecking at wood and other surfaces, protecting the brain from damage!6 Flickers and other woodpeckers often hit light poles and other metal objects, especially in the spring, as they are looking for the loudest sound they can, either to establish their territory, or to help attract a mate.3

Let’s look at three types of woodpeckers, and how their tongues are similar and different.

Northern Flickers have a very long sticky tongue (considered to be one of the birds with the longest tongues), with a single pointy barb on the end. The barb on the end of the tongue is a mobile tip that can change direction when probing deep into insect tunnels. There’s a tiny joint in the otherwise rigid tongue with two pairs of muscles inside the tongue inserting on tiny bones, enabling the barb to move in all directions.2 This helps it retrieve ants, grubs, and other insects. With their long tongues, they also don’t have to peck as far into wood. They have a keen sense of hearing, and once a bug is heard, they can peck to expose the location of the prey, and then slurp it up with their tongue, saving time and increasing the number of bugs eaten.

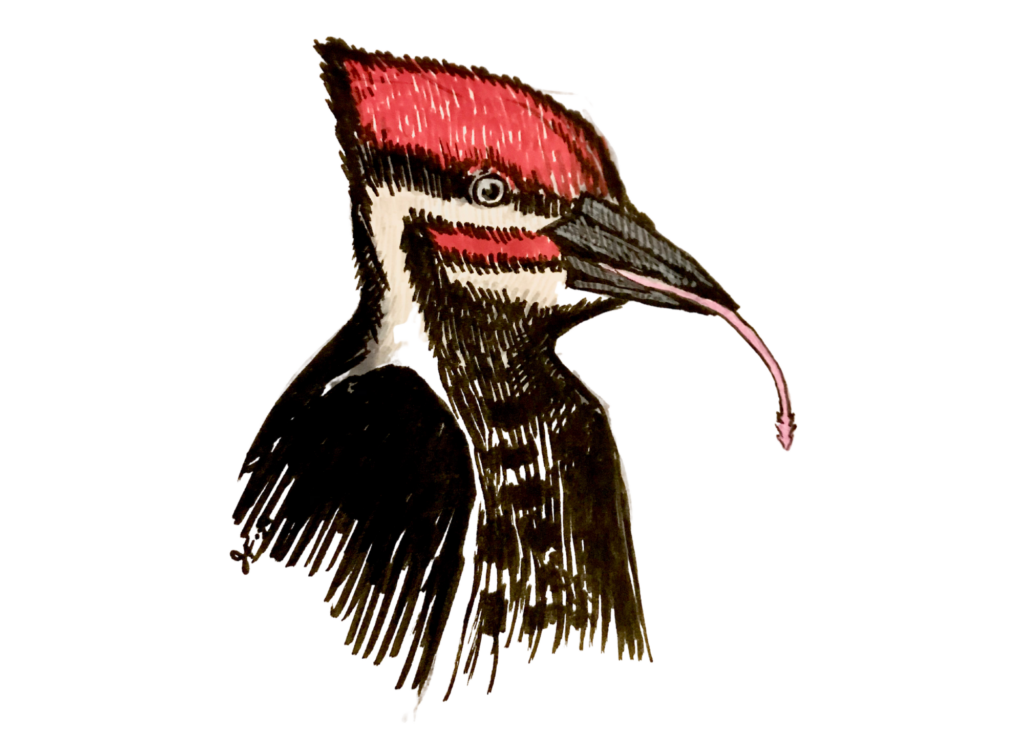

Pileated Woodpeckers also have a long sticky tongue, but instead of a single barb, it has multiple barbs on the end. They use their long tongues to explore tunnels and crevices, and the barbs help them retrieve prey from bark easier. Both Northern Flickers and Pileated Woodpeckers have salivary glands, protecting the mouth against germs and bacteria (all birds do), but as well as this protection, it produces a sticky spit that coats the tongue, furthering the possibility of getting prey.5 Birds lost their sweet receptor during evolution, but songbirds, hummingbirds, and woodpeckers have regained this ability (except the wryneck woodpecker that only eats ants). Taste buds are located at the base of the tongue.

Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers’ main diet is… You probably guessed it… sap! Their tongues, much shorter than the other woodpeckers we have discussed, reflect an amazing adaptation to help them retrieve sap (they don’t really suck the sap). Their tongues have tiny little brushes to help quickly absorb the sap via capillary action. Sapsuckers don’t have to dig deep into trees as they predominantly eat sap that has pooled up on the surface of the tree.4 As well as sap, they also eat the occasional insects from the short holes they drill in trees.1

And that’s just three types of bird tongues within one bird family! Imagine what other variations of tongues exist. I bet you will now – see the links below for more interesting facts on bird tongues!

Footnotes

-

- George Sranko, “Do Woodpeckers Tongues Wrap around the brain?” https://animalsfyi.com/how-woodpecker-tongues-work/

-

- Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Woodpeckers taste: sweet sap savoury ants https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2022/08/220819094528.htm

-

- James Morgan, “Why do woodpeckers peck on metal?” https://birdwatchingbuzz.com/why-do-woodpeckers-peck-on-metal/#:~:text=Birding%20experts%20believe%20that%20woodpeckers,compared%20to%20that%20of%20trees.

-

- Laura Erickson, “More About Bird Tongues than A Normal Person Would Want to Know” – https://blog.lauraerickson.com/2014/12/more-about-bird-tongues-than-normal.html

-

- Joseph O. Bourdane, Do Birds Have Tongues? (Also Taste Buds) https://birdingpoint.com/do-birds-have-tongues/

-

- Why Do Woodpeckers Resist Head Impact Injury: A Biomechanical Investigation https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0026490

Multiple writers: Lizhen Wang, Jason Tak-Man Cheung, Fang Pu,Deyu Li, Ming Zhang ,

- Why Do Woodpeckers Resist Head Impact Injury: A Biomechanical Investigation https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0026490